How Family Breakdown Hits Girls

Plenty of us are craving just one thing of permanence

The state of family breakdown in Britain is bleak. I read a statistic recently from Matt Goodwin’s Substack that by time they turn 14, 46% of first-born children here no longer live with both their mother and father.

Matt mentioned some other depressing statistics, too. Like this report looking at the percentage of British children who experience family breakdown by the time they turn 16/17: for those born in 1958, it was 9%. For those born in 1970 it had risen to 21%. And among children born around 2001-2002, it had risen almost five-fold to 43%.

Here’s what I know about family breakdown: it’s absolutely devastating for children. Children of divorce are more likely to be anxious, depressed and antisocial. They are more likely to end up in poverty. And perform worse in school. And turn to violent crime, drugs and alcohol abuse. And divorce themselves later in life. In fact, family structure has been shown to be the most significant demographic factor associated with suicide: those from divorced family structures have the highest suicide rates.

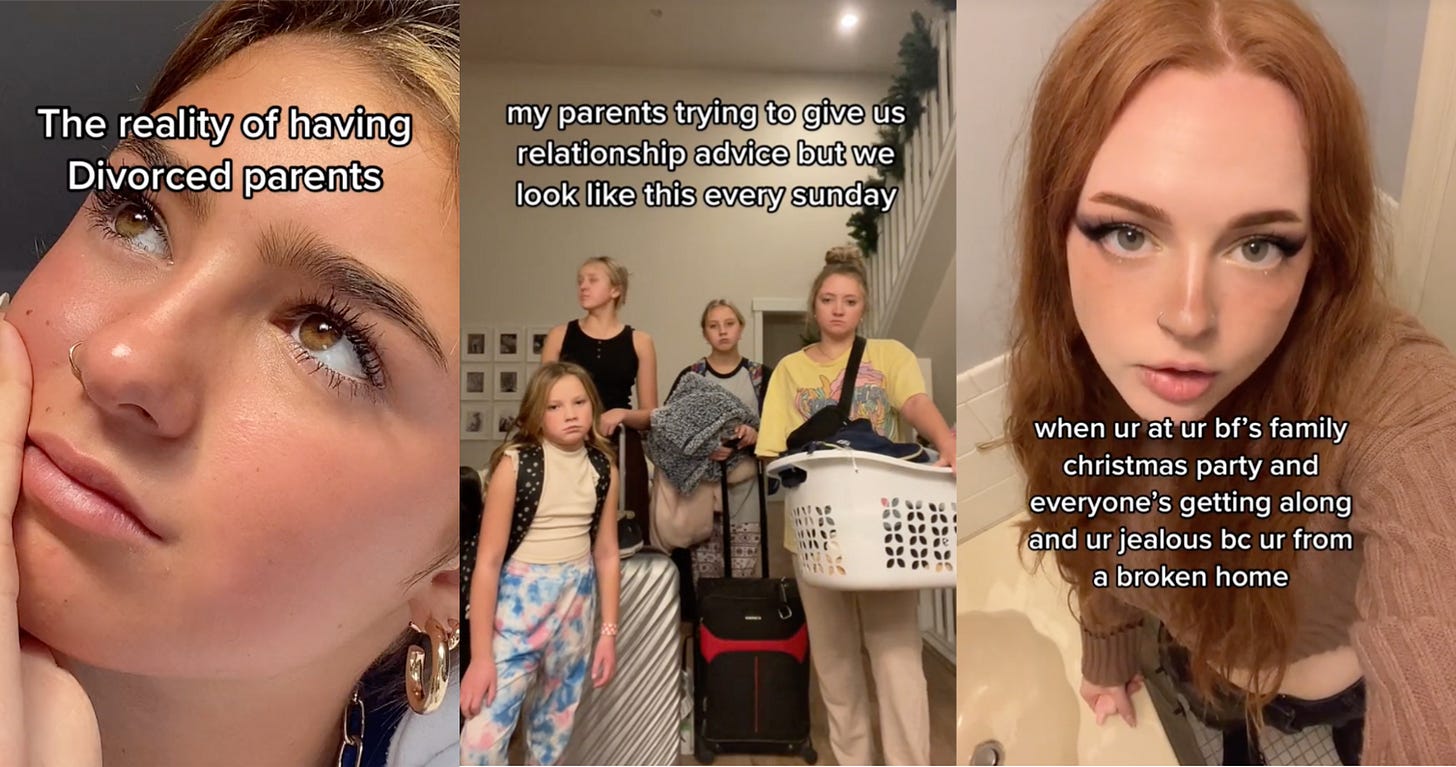

But what I’ve been thinking about lately is how family breakdown hit girls, specifically. I spoke with Brad Wilcox—fellow at the Institute of Family Studies and author of the forthcoming book Get Married—who told me that family breakdown does appear to affect boys and girls differently. “Boys usually respond to trauma by acting out — what psychologists call ‘externalising’ behaviour,” he explained. “Girls are more likely to respond to trauma by turning inwards—what psychologists call ‘internalising.’ So what we see is that rates of incarceration and school failure from boys at risk are especially high. By contrast, girls at risk are more likely to have high rates of anxiety and depression.”

Brad continued: “What I see in my ongoing research on family instability and gender is this: boys from non-intact homes are especially likely to end up floundering in school, to get suspended or expelled, and to end up incarcerated. Girls from non-intact homes are especially likely to report high rates of sadness.” From what I’ve read, too, there’s a lot of research linking family instability with these internalising symptoms in girls. Girls with divorced parents, for example, face an especially high risk of developing depressive symptoms in adolescence. Studies also show that girls from divorced and separated families suffer from lower self-esteem, are more likely to self-harm, and have a higher likelihood of developing eating disorders like bulimia and anorexia than those from intact families.

What’s alarming is that these are the exact issues reaching record-high levels among girls today. I often think about this crisis as a very internal one: girls gripped by anxiety, withdrawing socially, and channeling their emotional pain inwards, punishing themselves with behaviours like restricted eating and self-injury. Eating disorders, for example, are both surging and becoming more severe among girls in the UK and US. Self-harm rates, too, are soaring: since 2011 the UK has seen a 68% increase in rates of self-injury among girls aged 13 to 16. Then there’s all the girls being diagnosed with anxiety disorders, prescribed antidepressants and other mental health medications, and who say they feel persistently sad, hopeless, even suicidal.

Of course I’m not saying all of this is because of family breakdown. There are complex reasons for this crisis, which I’ve written about at length (social media, loneliness, the influence of the beauty industry, mental health industry, for a few). So it’s obviously not that simple. But what’s strange is how often we overlook family breakdown as a factor in all this, especially considering how closely the literature on family instability maps onto the mental health struggles millions of girls are currently facing.

Instead I’ve seen Gen Z’s mental health crisis blamed on, in my view, much more unlikely things. Personally I struggle to believe that girls are self-harming or starving themselves because of Trump. Or because of the climate crisis, or that they can’t get on the housing ladder. Not to say these things don’t matter — but I feel like we get so caught up in these distant, political causes we forget about what’s closer to home; what actually makes up most of girls’ intimate lives. Meanwhile, as Matt points out, trying to talk about traditional family structures today will have you pilloried as right-wing, regressive, even reactionary.

What’s also weird and ironic to me is that a progressive culture so well-versed in therapy-speak has this much trouble talking about family breakdown. Ours is a culture obsessed with trauma! We think we can get PTSD from university speakers and stupid jokes and election results. And yet it’s also a culture which largely ignores and even glamorises what seems to me one of the most obvious traumas of all?? If anything qualifies as traumatic—as in, an emotionally distressing event that leaves a lasting impact—surely it’s family breakdown, which really does seem to stay with people, shape their view of love and life and just keep playing out, over and over?

This is how I see it: even if there are other factors, which there certainly are, aren’t all of those things made worse by family breakdown? Social media is terrible for girls, but surely it’s worse when your family is falling apart? Surely that makes you more likely to spend time online, seek validation from strangers, and surrender your self-worth to these platforms? And I don’t doubt that there are girls worrying about climate change and the future — but aren’t you just more likely to be anxious and neurotic about these things without a firm foundation to ground you? I guess I think of it like this: life has always been traumatic and scary and unpredictable, but what makes all that far easier is having a stable family to fall back on. And that’s what more and more girls are growing up without: that solid base from which they can find strength, resilience and healthier coping strategies.

So family breakdown matters. And you shouldn’t have to be right-wing or religious to recognise that. This isn’t something we can afford to politicise or cede to the culture wars; it’s common sense: of course kids need stability, of course sometimes it’s better for parents to break up but we all know most of the time it isn’t. And no it’s not old-fashioned or regressive to talk about it now — if anything it’s more important in the modern world, where we are all so flooded with constant, fleeting distractions and instant gratification and this cultural push to treat everything and everyone as temporary and discardable, and in which I think plenty of us are craving just one thing of permanence.

Because a generation of girls is falling apart. And I think for many those cracks, those fissures, formed in their childhoods, where they learnt they couldn’t trust, couldn’t settle, couldn’t courageously venture into the world without their foundations collapsing beneath them. Yes, this crisis is complicated. But I think we could make more sense of it if we at least admitted that, for a lot of these girls, they weren’t the first to fall apart. Their families were.

This is tough for me, as a divorced father of two girls. Since this is public and I use my handle in a number of spaces, I’ll just say that we got divorced for reasons that were worse than “We were bored of each other” (literally something a friend told me about her divorce once) but way less bad than any kind of abuse.

But once that decision was made, we tried to do everything right. We had 50-50 custody. We hammered out the divorce agreement in a single day with the mediator. Child support was never a problem. We worked together on every issue. We didn’t badmouth the other person. We sat together at the kids’ sports games. My youngest likes to tell the story of texting her sister , on a day when she was switching houses, saying, “I hate that our parents get along so well. I’m cold and want to go home and they’re still talking to each other. Why can’t they hate each other like other divorcees?” (Joking, obviously)

But even with all that... it sure didn’t help their psyches, particularly our eldest. In some ways, this was how difficult it is to keep a consistent message to your children (notably, when sexuality raised its head as it does with the pubescent) when you aren’t in the same house and can’t put together a unified front; you don’t know what the other is saying, and so a consistent message gets garbled. But even worse, and hardest on them both, was having the bedrock of their lives taken away from them. We were a pretty stable family, and to lose that sense of support and permanence really messed them up and left scars that never fully healed.

They’re both doing pretty well, all things considered, and that’s partly because of the work we put into keeping the divorce amicable, partly because of their innate temperament and resilience, and (tbh) partly because they’re moderately privileged and it seems like the hit to socioeconomic status is responsible for a lot of the harms associated with divorce. But yeah. I can see the harm it did. It’s hard.

Yes, I read Matt's shocking statisticsthe other day too. "As Matt points out, trying to talk about traditional family structures today will have you pilloried as right-wing, regressive, even reactionary." Therein lies the problem. Young people are so removed of the possibility of marriage with few role models for a traditional, healthy, archetype of a relationship. In their eyes, the negatives outweigh the positives; i.e. marriage as slavery, domestic servitude, giving up their freedom. It is incredibly sad.

I still remember my Grandparents, other members of my extended family, even family friends and neighbours having stable, happy, healthy marriages. They were having a lot of fun and joyful times.

Commitment seems to be the idea young people are afraid of. The hook-up culture is testament to this. Short-term gratification and sex as a commodity, made too easily accessible via 'dating' apps. Of course, nobody uses dating apps for 'dating' - it isn't a tool to find a life-long partner. I suppose my views too, would be considered right-wing...