The Future Of Beauty Is Already Here

We've been living as virtual avatars for years

It was recently the world’s first Metaverse Beauty Week. Beauty brands like Lush, Neutrogena and Glossybox came together for the five-day virtual event, marketed under the slogan Reality Gets a Makeover. Hosted across various metaverses, MBW offered all kinds of immersive experiences. You could play interactive beauty games. You could “try on” make-up using AR filters. And, something new to me, you could collect virtual beauty products for your avatar.

In other words: brands now want us to buy products to make our avatars more attractive! There were virtual versions of SPF serums and body creams. There were digital brow pencils, eyeliners and freckle tints. One Gen Z brand even debuted a digital hair shine spray to let “your avatar transform into the glowing goddess it deserves to be.”

Apparently this is happening elsewhere, too. Estée Lauder recently announced a digital version of their Advanced Night Repair anti-ageing serum to give your avatar a “virtual glow.” Other big brands like L’Oréal, Johnson & Johnson and Fenty Beauty have already filed trademarks for digital beauty products, from skincare creams to sun-care to virtual perfumes.

At first I was sceptical. Would anyone really want these? Marketing for Metaverse Beauty Week insisted this was a groundbreaking event, a subversion of beauty standards, that I should get ready to immerse myself in a revolution. The “next frontier for the beauty industry” — the “future of beauty”! But seriously. A serum for pixellated skin? A hair conditioner for a glitchy cartoon alien?? Surely nobody would actually pay for their virtual avatars to look attractive?

But then again, they already do. The more I thought about it, the more I realised that this isn’t anything new or surprising at all. We’ve been obsessing over the appearance of our online avatars for years.

In fact, we’re over a decade into this now. In 2013, the editing app FaceTune came out and taught girls like me how to smooth our skin, cinch our waists, and reassemble our prepubescent faces and bodies. In 2016, Snapchat introduced face filters that seemed like innocent puppy ears and flower crowns — but were subtly chiselling our cheeks, airbrushing our skin, and acclimating us to our avatars. I got used to the virtual version of me. I liked her. I lived through her. And millions of girls did the same, spending the most formative years of their lives digitalising and modifying themselves: learning to hate their real reflections; falling in love with the fake version. “Transform the way you look!” Snapchat told us. “Put your best face forward!” said FaceTune. And so we did.

So much so, actually, that I think some of us now care more about how our virtual avatars look than how we actually look.

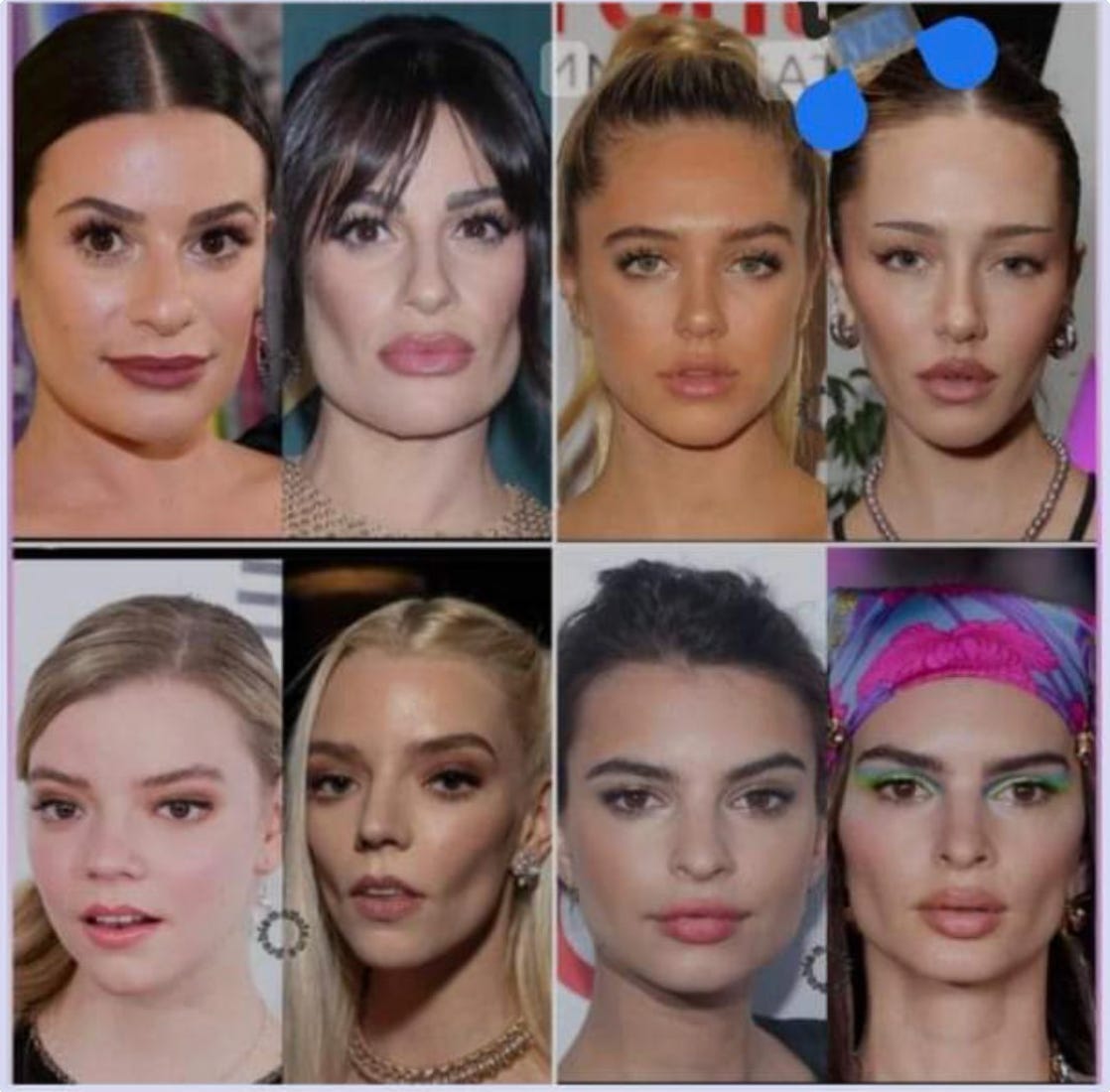

Think about it: so many popular cosmetic procedures and beauty trends today look better online than they do in real life. First there was the Kardashian-esque, super-contoured makeup (“Instagram Makeup”) in the mid-2010s, which famously looks flawless on camera and excessive in real life. Then the lip fillers: mostly doll-like online; often duck-like in-person. Next the Instagrammable Brazilian Butt Lifts (BBLs), and now procedures like buccal fat removal—a surgery that removes fat from your cheeks—which tends to look sexy and sultry on camera, but skeletal in reality. “Buccal fat removal…is optimized to offset lens contortions,” the writer Salomé Sibonex tweeted recently, “That’s the strangest thing about it: you’d have to get more pleasure from seeing yourself via camera footage than in a mirror to want this.”

Point being: there is already a massive market for consumers who care more about their virtual appearance than they do their actual appearance. As Salomé writes: “Women are adapting beauty preferences not for the people in front of them, but for the people who see them on screens.”

Beauty influencers are, of course, the best example. For years they’ve been modifying their faces and bodies to look better on camera. And what’s interesting is that they constantly face backlash for looking different in real life to how they do online. There’s all these Insta vs. Reality exposé pages on Reddit and reaction videos on YouTube comparing candid, unedited photos of influencers with their photoshopped posts. They call out everything from botched BBLs to overdone makeup to obvious facial fillers. And these forums and videos are always filled with comments like “literally how are they NOT embarrassed?” and “does she realise people will see her in real life?”

But what if they’ve got it wrong? Maybe the question isn’t whether these influencers recognise the difference between how they look online and in reality. It’s whether reality even matters to them. Because everything that is real in their lives—their career, income, sense of identity, belonging, self-worth—exists online. They do their makeup for Instagram. They tailor their lifestyles for TikTok. And they inject and chisel away at and pump their faces with silicone not for real people to look at and admire, but a virtual audience to like and validate. In the battle between Insta vs reality, Insta has already won.

And the truth is it isn’t just influencers anymore. For an entire generation of kids today, the virtual world is far more real than reality. Gen Z spends around 10.6 hours a day consuming online content. Teens who meet up with friends “almost every day” is down from from 50% in the ‘90s to 25% today. Pre-teens say they talk more online, feel more like themselves, are more at peace. In real life they feel awkward, mute, invisible. And so for many young people the physical world is rapidly becoming nothing but a backdrop for the virtual world. Beaches and sunsets are backgrounds for Instagram posts. Friends are props to take selfies with. Experiences and memories are condensed into content. And modifying their faces and bodies in real life is sort of like the Sims customise avatar page: a loading screen before they enter the real, online world, the place where they really want to look good.

This isn’t an exaggeration. I mean, a Gen Zer interviewed to promote Metaverse Beauty Week put it this way: “I work from home so mainly see my colleagues on Zoom and have loads of friends that I only really see on Snapchat or Instagram stories,” she said. “Really, most of my generation spends the majority of our time online…so having things like cyborg filters or alien skins…which more accurately represents what we wished we looked like (in my case at least), is epic.”

It’s bleak. But predictable. We are a generation that came of age alongside this growing commercial machine that insisted we invest more and more time into our virtual selves, and rewarded us with likes, followers and validation when we did. It was always there, always tapping into our lucrative supply of pre-teen insecurity and self-loathing, always promising us we could transform into someone else; someone perfect. So, no. There’s nothing new or revolutionary about brands selling digital hairsprays and lipsticks. And it’s no surprise that we want them. We’ve been living as virtual avatars for years.

Let’s not pretend, then, that Metaverse Beauty Week is “subverting beauty norms”. It isn’t subverting anything. It’s just another push to surrender more of ourselves to the virtual world, another step on a road we’ve been on for a long time, straddling two worlds, sliding toward total virtual disembodiment. This isn’t the “future of beauty”; it’s already here. So when you see a woman with overfilled lips, unflattering makeup and maybe even a botched BBL, you might think she doesn’t look good. But she does. Just not in this world.

Another banger article

Insightful but.... can you really be missing the connection here between living ones life online as an always-editable looks-conscious avatar....and a generation that thinks you can be any gender you want (or no gender) at any time, in defiance of biological reality?